PDF of this entire webpage 26 May 2025

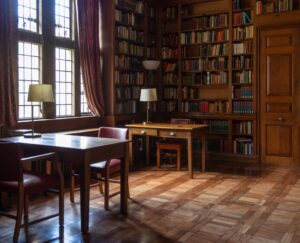

At Campion Hall and Blackfriars, Oxford

Important Reminder: Non residents are required by the UK to complete and submit the ETA form. Some countries’ nationals (including the USA) will be required to pre-register or risk a long line at the border. Others, such as EU nationals, may optionally register. Full information is available by the following link. The application is quick and costs only 10 GBP: Link.

Philosophy in the Abrahamic Traditions

Oxford, UK 29-31 May 2025 (with a pre-conference graduate student day 28 May)

Organized by the Aquinas and ‘the Arabs’ International Working Group

The 2025 AAIWG Summer Conference hosted by our member Dr Daniel DeHaan, Frederick Copleston Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer In Philosophy and Theology in the Catholic Tradition, Campion Hall and Blackfriars, University of Oxford. The event is organized by Dr DeHaan, Prof. Luis X. López-Farjeat (Universidad Panamericana) and Prof. Richard C. Taylor (Marquette University & KU Leuven), with the assistance of Prof. Brett Yardley (DeSales University) and Prof. Nathaniel Taylor (The Catholic University of America).

The entire event will take place over four (4) days. On 28 May we have a special day devoted to graduate student mentoring. The Conference itself will be 29-31 May. The second of the three days is specifically devoted to the topic of the influence of philosophy in the lands of Islam on the development of philosophical and theological thought in Europe.

Submissions: The CALL FOR PAPERS opens 1 December, closing 10 January. The intention is that the program be announced ca. 15 February 2025. Each submission should include a statement on whether it is tentative (e.g., dependent on procuring funding, et al.) or a firm commitment to attend if accepted by the Scientific Committee. Submissions are now closed.

Membership in the AAIWG is not necessary but some priority may be given to submissions by members.

NOTE: All participants are expected provide for their own costs of their travel, housing and other expenses.

For the conference 29-31 May established scholars and post-docs should submit a title and a short descriptive abstract of 100 words to aaiwgscholarssubmissions@gmail.com. Recent Ph.D recipients and post-docs should submit a current CV.

For the graduate student workshop 28 May, students should submit a title and a short descriptive abstract of 100 words to aaiwggradstudentsubmissions@gmail.com. These graduate student proposals require that a letter of support be submitted by the student’s supervisor to the same email address in the previous sentence.

Need other information? Contact Richard Taylor at richard.taylor(at)marquette.edu or richard.taylor(at)kuleuven.be.

Selected Presenters: You are responsible for providing copies of any handouts for your audience.

Meetings will be at Blackfriars and Campion Hall. ChatGPT says the following:

“The walking distance from Campion Hall to Blackfriars on St Giles in Oxford, UK, is approximately 0.5 miles (about 10 minutes). The exact time may vary depending on your walking speed and the route you take.

To get there:

- Exit Campion Hall (on Brewer Street) and head north on Brewer Street toward the High Street.

- Turn left onto the High Street and walk west.

- Continue along the High Street and take a right onto St Giles.

- Blackfriars will be a little further down on your right.

It’s a relatively short and straightforward walk.”

Travel: We recommend NOT FLYING TO STANSTED. It is great for Cambridge, but Stansted airport is very inconveniently located for getting to and from Oxford. To/From Oxford and Heathrow or Gatwick we recommend: https://www.theairlineoxford.co.uk/.

Housing options: see below.

Conference locations overview

We are at Campion Hall on Wednesday May 28 for the graduate student day and will be in the 1st floor seminar room by the chapel (meaning it’s 1 floor going up the stairs) .

We are at Campion Hall on Thursday May 29 on the ground floor lecture room by the entrance. The dinner that night at 19:00 is also in Campion Hall. (Vegetarian option available.)

We are at Blackfriars only one day. On Friday May 30 in the Aula. The wine reception will also be in this room at the end of the day.

We are at Campion Hall again on Saturday May 31 on the ground floor lecture room by the entrance.

Aside from the Conference Dinner Thursday 29 May, participants will be on their own for breakfasts, lunches and dinners.

Schedule for Graduate Student Colloquium 28 May 2025

At Campion Hall

(First floor seminar room by the chapel, meaning it’s 1 floor going up the stairs)

Is Powerpoint use available? Yes.

28 May schedule for graduate student presentations

Format: 25-30 min. presentation, 15 or 20 min. discussion, total 45 min. NOTE: Timed alarms will be set to 25 min. (first alarm) and 30 min. (final alarm for end of oral presentation).

ChatGPT says: “In 25–30 minutes, you can expect to read out loud between 3,250 and 4,800 words, depending on your speaking speed and comfort with the material.” But yours will be philosophy papers so we advise against speed reading and suggest presentations of 3000-4000 words.

We would also suggest that you bring a handouts with an outline and your name, title, email address.

8:45 welcome and introductions

Morning Session Chair: Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University & Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

• 9:00-9:45 (1) Alexander Schmid, Louisiana State University, “Dante, Islamic-Judaic Rationalism, and the Doctrine of Double Truth”

• 9:45-10:30 (2) Saad Ismail, Oxford, “Avicenna and Knowledge-First Epistemology.”

• 10:30-11:15 (3) Nicoletta Nativo, Charles University, Prague, “Albertism and Averroism in the Paduan Renaissance: Zimara vs Nifo”

11:15-11:45 break

• 11:45-12:30 (4) Ivonne María Acuña Macouzet, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City, “The Relationship between Philosophical Ta’wīl and Averroes’s Jurisprudence

• 12:30-13:15 (5) John G. Antturi, University of Helsinki, “Aquinas on the individuality, universality, and incorporeality of human intellectual cognition”

13:15-14:45 lunch (possibly at Fernando’s Cafe short walk away)

Afternoon Session Chair: Prof. Luis López-Farjeat, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City

• 14:45-15:30 (6) Doha Tazi Hemida, Columbia University, “An Ash’arite Theology of Property” (*)

• 15:30-16:15 (7) Zahra Nayebi, University of Freiburg, “Being, Non-Being, and Essential Possibility: A Metaphysical Perspective on al-Fārābī’s Refutation of Parmenides” (pending)

• 16:15-17:00 (8) Keramat Varzdar, University of Tehran, & Sajad Amirkhani, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, “Individuation Misread: A Critical Study of Mullā Ṣadrā’s Interpretation of al-Fārābī” (pending)

17:00 Closing remarks and open discussion.

17:30 Time for some wine or other beverages! (??The Bear Inn?? La Taberna??)

Graduate student presentation abstracts see below

29 May 2025 Colloquium on Philosophy in the Arabic and Hebrew Traditions

Conference Presentation Schedule

Is Powepoint available for these three days of the Conference? Yes, at both locations.

Procedures: Each presenter will have 40-45 minutes to speak and will be warned at 40 min. After 45 min. the speaker’s presentation will end and the floor will be open for questions and discussion. For presentations ending in less than 45 min. there will be more time for questions and rich discussion. All sessions will be for 55 min. only, with the exception of (7), the Special Session on Method at 17:20 on Friday 29 May.

AI tells us: “It will take approximately 31-44 minutes to read a 4400-word paper aloud. This is based on an average out-loud reading speed of 125-183 words per minute.” Please plan accordingly.

At Campion Hall

(Ground floor lecture room by the entrance)

9-9:30 Welcome: TBA

Note that with the exception the special final event for this day we will follow this procedure:

Timed alarms will be set to 40 min. (first alarm) and 45 min. (final alarm for end of oral presentation) to allow for 10-15 min. for discussion and questions. The total time for each presentation including discussion and questions is 55 min.

AI tells us: “It will take approximately 31-44 minutes to read a 4400-word paper aloud. This is based on an average out-loud reading speed of 125-183 words per minute.” Please plan accordingly.

Chair: (i) Prof. Frank Griffel, Professor for the Study of Abrahamic Religions, Fellow at Lady Margaret Hall,

University of Oxford

9:30-10:25 (1) Dr. Therese-Anne Druart, Prof. Emerita, The Catholic University of America, “Al-Fārābī”s and Ibn Sīnā”s Problematic Conception of Justice “

10:25-11:20 (2) Prof. Yehuda Halper, Bar-Ilan University, Israel, “Will the Wise Man Boast of Al-Fārābī? How Samuel Ibn Tibbon Slipped Parts of De Intellectu into his Explanation of Unusual Terms in Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed” “

11:20-11:50 Break

Chair: (ii) Dr Steven Harvey, Professor Emeritus, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

11:50-12:45 (3) Prof. Irfan Omar, Marquette University, “Abū’l ‘Alā’ al-Ma‘arrī’s Philosophical Critique of Religion”

12:45-13:35 (4) Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, USA, and KU Leuven, Belgium, “A Critical Consideration of Ibn Rushd on Matters of Philosophy and Religion “

13:35-15:00 Lunch Break

Chair: (iii) Prof. Yehuda Halper, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

15:00-15:55 (5) Prof. Brett Yardley, DeSales University, “Can ‘Pseudo’ Authors be Trusted?”

15:55-16:50 (6) Dr Steven Harvey, Professor Emeritus, Bar-Ilan University, Israel, “H. A. Wolfson and the Aquinas and ‘the Arabs’ Project”

16:50-17:20 Break

17:20-18:45 (7) Special Session on Method.

Chair: (iv) Prof. John Marenbon, Cambidge University

Prof. Katja Krause, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science & Technical University, Berlin, “Method in the History of Medieval Philosophy: What Good does it Serve?” Commentator: Prof. Frank Griffel, Oxford

19:00 Conference Dinner at Campion Hall (by confirmed reservation only)

At Blackfriars

(in the Aula.)

30 May Colloquium on the Influence of Philosophy in the Lands of Islam on European Thought

Timed alarms will be set to 40 min. (first alarm) and 45 min. (final alarm for end of oral presentation) to allow for 10-15 min. for discussion and questions. The total time for each presentation including discussion and questions is 55 min.

AI tells us: “It will take approximately 31-44 minutes to read a 4400-word paper aloud. This is based on an average out-loud reading speed of 125-183 words per minute.” Please plan accordingly.

Chair: (v) Prof. Luis López-Farjeat, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City

9-9:55 (8) Dr. R. E. Houser, Prof. Emeritus, University of St Thomas (Houston), “First Steps onto the Five Ways: Thomas and Avicenna”

9:55-10:50 (9) Prof. David B. Twetten, Marquette University, “Aquinas’ Novel Definition of ‘Universal’ and Its Background in Avicenna: How to Answer ‘Universal Realism’ “

11:50-11:20 Break

11:20-12:25 (10) Prof. John Peck, S.J., Saint Louis University, “Thomas Aquinas’s Prime Matter Pluralism “

12:25-13:20 (11) Dr. Daniel DeHaan, Oxford, “God, Creation, and Providence: Avicenna’s Influence on the Structure of the Contra Gentiles“

13:30-15:00 Lunch

Chair: (iv) Prof. David B. Twetten, Marquette University

15:00-15:55 (12) Prof. Randall B. Smith, University of St Thomas (Houston), “The Natural Law and Thomas Aquinas’s Debt to Maimonides”

15:55-16:50 (13) Prof. Patrick Zoll, S. J., Munich School of Philosophy, “Can We Know the Essence of a Simple God? Thomas Aquinas’s Critique of Maimonides in De potentia“

16:50-17:20 Break

17:20-18:15 (14) Dr. Marta Borgo, Commissio Leonina, Paris, & Dr. Mostafa Najafi, Lucerne University,”Ibn Rušd’s Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics V.7 and Its Impact on Medieval Conceptions of Being as True”

18:15-19:10 (15) Prof. Nader El Bizri, Dean of the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences at the University of Sharjah, heading the Falsafa Project of the Knapp Foundation, “Alhazen’s Optics and its impact on science and the architectural visual arts in Europe”

19:10 in the Aula: Knapp Foundation Wine Reception with remarks by Prof. Laurence Hemming, honorary professor jointly in Lancaster University’s Philosophy, Politics and Religion Department, and the Lancaster University Management School and Knapp Foundation Director

31 May 2025 Colloquium on Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure, Philo and More

At Campion Hall

(Ground floor lecture room by the entrance)

Timed alarms will be set to 40 min. (first alarm) and 45 min. (final alarm for end of oral presentation) to allow for 10-15 min. for discussion and questions. The total time for each presentation including discussion and questions is 55 min.

AI tells us: “It will take approximately 31-44 minutes to read a 4400-word paper aloud. This is based on an average out-loud reading speed of 125-183 words per minute.” Please plan accordingly.

Chair: (v) Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, USA, and KU Leuven, Belgium

9-9:55 (16) Prof. Adam Takahashi, Kwansei Gakuin University (Nishinomiya, Japan), “Albert the Great on Angels and Miracles: Providence and Natural Causality in his Commentary on the Sentences (Book II) “

9:55-10:50 (17) Dr. Andre Martin, Post Doctoral Fellow, Charles University, Prague (PhD, McGill 2022), “Averroes’ Agent Sense in the Early 13th Century: Albert and his Sources”

11:00-11:30 Break

11:30-12:25 (18) Dr. Tracy Wietecha, Technical University, Berlin, “The City as A Mirror of Virtue: The Influence of Averroes on Albert the Great’s Conception of Virtue”

12:25-13:20 (19) Dr. Edmund Lazzari, Duquesne University, “Reading the Book of Nature: Quranic and Bonaventurian ayāŧ/similitudines of God in Nature”

13:30-15:00 Lunch

Chair: (vi) Dr. Therese-Anne Druart, Prof. Emerita, CUA

15:00-15:55 (20) Prof. Luis López-Farjeat, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City, “The literal (ῥητή or φανερά / ẓāhir) and the hidden (ὑπόνοια / bāṭin) in Philo of Alexandria and the Islamic philosophical tradition”

15:55-16:50 (21) Dr. Francisco J. Romero Carrasquillo, St. Gregory the Great Seminary , Seward, Nebraska, “The Multiple Meanings of Sacra Doctrine in Aquinas Seen Through Averroes’ Doctrine on the Levels of Discourse”

16:50-17:45 (22) Dr. des. Ibrahim Safri , Universität Heidelberg, “Motion in Categories in Pre-modern Islamic Philosophy”

17:45 Final discussion and closing remarks. Chairs: Richard Taylor & Luis López-Farjeat

Abstracts of Presentations

(incomplete, more forthcoming)

Graduate Student Presentations 28 May 2025

Sajad Amirkhani, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, & Keramat Varzdar, University of Tehran

“Individuation Misread: A Critical Study of Mullā Ṣadrā’s Interpretation of al-Fārābī”

John Antturi, University of Helsinki, Finnland

“Aquinas on the individuality, universality, and incorporeality of human intellectual cognition”

I examine how Aquinas’s argumentation for the subsistence and incorporeality of the human soul evolves as a result of his opposition to Averroes’ view that all humans share one Material Intellect. In early works, Aquinas is happy to speak of “universal forms” and the “universal being” of the human intellect. Later on, he adopts a clearly deflated view of the universal mode of human intellectual cognition which preserves its individual mode of being. I argue that this deflationism leads to one aspect of the “content fallacy” problem for Aquinas and present a novel solution to it.

Ivonne María Acuña Macouzet, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City, Mexico

“The Relationship between Philosophical Ta’wīl and Averroes’s Jurisprudence”

This presentation examines the concepts of inference and analogy in Averroes’s logical works to show how both concepts are used in his juridical treatises. Based on the Middle Commentary on the Rhetoric, the Abridgement of al-Ghazālī, and The Distinguished Jurist’s Primer, I aim to show how the qiyās as the jurists use is in most cases a metaphor, and how the interpretation of the Law is precisely a metaphorical interpretation of the text. The examination of those terms used in Averroes’s logical and juridical works shows the latter’s importance in understanding the philosophy of Ibn Rushd and the original ways in which he applied the Aristotelian logic to other disciplines.

John G. Antturi, University of Helsinki, “Aquinas on the individuality, universality, and incorporeality of human intellectual cognition”

R. E. Houser, “First Steps onto the Five Ways: Avicenna and Aquinas”

Abstract

In writing his Scriptum Thomas added the rational authority of demonstrative science, using principles known through reason. So he began with his own prologue that presented theology as a “science” built on principles known through both faith as well as those known through reason. To prove ‘God exists’ rationally Thomas turned, not to Aristotle but to the Scientia Divina (or Metaphysica) of Avicenna’s Book of Healing, which he had read as an Arts student at the University of Naples. There Avicenna first proposed using all four causes, as principles known through reason, in order to prove God exists. But in testing out the causes, Avicenna concluded that only an argument from the efficient cause, not of nature or essence, but of existence (esse, wujud), could be demonstrative. So Thomas turned to Dionysius the Areopagite, in order to follow Avicenna’s original plan using all four causes, in taking his very first steps onto the five ways.

Saad Ismail, Avicenna and Knowledge-First Epistemology.

Abstract:

Recent scholarship has highlighted parallels between contemporary Knowledge-First epistemology

and classical philosophical traditions. This paper examines whether Avicenna’s theory of knowledge

anticipates Timothy Williamson’s Knowledge-First approach. While both thinkers maintain

knowledge is irreducible to belief, I argue Avicenna’s epistemology diverges fundamentally from

Williamson’s due to his distinctive metaphysics of mind and perception. Focusing on Avicenna’s

conception of taṣawwur (conception) and taṣdīq (assent) in his logical works, I demonstrate how

his dualist psychology and prioritization of non-propositional cognition preclude straightforward

comparison with Knowledge-First theories, while still offering novel insights for contemporary

epistemology.

Doha Tazi Hemida, PhD student, Columbia University,

“An Ash’arite Theology of Property”

This paper elucidates the definition of justice (ʾadl) Shahrastānī attributes to the Ashʾarī school: justice is nothing less than God “freely disposing of his property and his sovereign dominion (mutaṣṣarrif fī milkihi wa-mulkihi).” Why do Ashʾarites consider God’s condition as absolute owner of all things to be the source of the differentiation between good and evil, between justice and injustice How does this theology of property shape the nature of reality and morality? This paper delineates the various theological-philosophical tensions and concepts against which this Ashʾarite theology of property emerged (i.e. “generosity” (jūd) and “purpose” (gharaḍ) as understood by Muʾtazilites and Neoplatonists; Qāḍī ʾAbd al-Jabbār’s anti-Ashʾarite refutation)

Zahra Nayebi, PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Freiburg, Germany

“Being, Non-Being, and Essential Possibility: A Metaphysical Perspective on al-Fārābī’s Refutation of Parmenides In his critique of Parmenidean monism”

Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī (d. 950) recognizes two false presumptions in Parmenides’ theory: first, that “being” is a univocal term, and second, that “non-being” signifies absolute nothingness. In response, al-Fārābī introduces two senses of being —being as what is set apart by a whatness outside the soul and being as true — and examines how each sense can be negated in different ways. In this presentation, first, I will

analyze how al-Fārābī’s senses of being and non-being intersect with his theory of potentiality

and actuality, and his account of “essential possibility”. I will then demonstrate how this theoretical framework sheds light on his refutation of Parmenides.

Nicoletta Nativo, PhD student in Philosophy at Charles University, Prague

Title: “Albertism and Averroism in the Paduan Renaissance: Zimara vs Nifo”

Abstract:

The Paduan Renaissance displayed an interest in earlier medieval thinkers such as the Latin Averroes, Albert the Great, and Scotus. This intellectual revival is exemplified by Marco Antonio Zimara’s Quaestio de speciebus intelligibilibus ad mentem Averrois (1506), written against Agostino Nifo. Unlike Nifo and the moderni, Zimara defends a more traditional interpretation of intelligible species, which he attributes to Albert – whom he curiously esteems the greatest “Averroist” – and to Averroes himself. Zimara critiques Nifo’s misinterpretation of both authorities, leading to a conflict between competing readings of Averroes and thus offering new insights into Albert’s legacy in Renaissance Scholasticism.

Alexander Schmid, Doctoral Student in Comparative Literature and Political Science at Louisiana State University

Dante, Islamic-Judaic Rationalism, and the Doctrine of Double Truth

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, he portrays a unique vision of the Christian afterlife at the literal level. What if Dante, like the Jewish, Muslim, and Latin Averroists of his time, however, wrote esoterically and himself adopted a doctrine of double truth? In this essay, I will explore the Islamo-Judaic and Latin Averroistic influences on Dante’s thought to show that he is much more of an Averroistic thinker via Ibn Tibbon than he is a traditional scholastic who maintains the 13th century Parisian conceit of subordinating philosophy to theology. This work will continue and expand recent work by Greg Stone, Paul Stern, and Jean-Baptiste Brenet.

Senior Presentations 29-31 May 2025

Marta Borgo, Leonine Commission, Paris, France / University of Lucerne, Switzerland, and Mostafa Najafi, University of Lucerne

“Ibn Rušd’s Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics V.7 and Its Impact on Medieval Conceptions of Being as True”

In this paper, we examine Ibn Rušd’s reading of Aristotle’s Metaphysics V.7, focusing on‘being as true,’ and its reception in the Latin tradition. After highlighting the different perspectives on truth as a property of propositions and/or extra-mental things, we explore the relationship between veridical and per se being with respect to the notions of essence and existence. Thus, we analyze different classifications of the senses of being within this chapter, and situate V.7 within Metaphysics. By considering the (re)constructions of the notion of being from Arabic into Latin, we show how some 13th-century thinkers transformed

Daniel DeHaan, Blackfriars, Oxford, UK

“God, Creation, and Providence: Avicenna’s Influence on the Structure of the Contra Gentiles“

In this presentation I argue that the major divisions of the philosophical theology books of Aquinas’s Summa contra gentiles are inspired by the final three books of Avicenna’s Metaphysics of the Healing. Aquinas encountered in Avicenna’s own philosophical summa a rigorous philosophical theology as the ultimate goal of metaphysical enquiry into being as being. Many of the arguments and conclusions of Avicenna’s philosophical theology Aquinas appropriated and elaborated. But Aquinas also found theses which he rejected on both philosophical and revealed theological grounds. The first three books of the Contra Gentiles, I show constitute, in part, Aquinas’s own response and philosophical theology alternative to Avicenna’s systematic conclusions concerning God’s existence and essence (Book VIII), the necessity of God’s creation of the emanated order (book IX), and its providential return to God (book X).

Thérèse-Anne Druart, The Catholic University of America, USA

“Al-Farabi’s and Ibn Sina’s Problematic Conception of Justice”

Both al-Farabi and Ibn Sina struggle to elaborate a conception of justice and speak little of it. First, they have trouble unifying Plato’s and Aristotle’s conceptions. Second, they find challenging to determine the exact relation justice has to the mean. Is it a virtue that helps determine what the mean is for the other virtues or is it a mean between two contraries as the other moral virtues are? Finally, they accept the division of practical philosophy into ethics dealing with the single human being, and household management and politics as both dealing with relationships with other people. If one restricts ethics to relationships with oneself only, then is justice excluded from ethics proper? Did they manage to resolve the tensions?

Nader El Bizri, Senior Research Fellow at the Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Studies, University of London, Senior Fellow at the Knapp Foundation,, and a longstanding Affiliated Scholar with the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge

Yehuda Halper, Bar Ilan University, Israel

“Will the Wise Man Boast of Al-Fārābī? How Samuel Ibn Tibbon Slipped Parts of De Intellectu into his Explanation of Unusual Terms in Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed“

The first translator of Moses Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed, Samuel Ibn Tibbon compiled a companion volume to explain the difficult concepts of Aristotelian philosophy to a Hebrew speaking readership that had no other access to Aristotelian thought. This work, which took shape as an alphabetically ordered explanation of terms, included notes that Samuel had written in the margins of his translations along with translated and recompiled sentences from a host of other works. Here I shall argue that the explanations of eleven terms on intellect and soul are actually translated and edited sections of Al-Fārābī’s Arabic De Intellectu. Samuel not only translates sections of this work, but explains how they fit in with Maimonides’ theory of intellect in the Guide and the angelology presented in the Code of Law (Mishneh Torah). Not only was Samuel’s pioneering work nearly simultaneously replicated in Hebrew by another author, Dominicus Gundissalinus also translated the same work into Latin and strove to integrate its principles into his own theology. Thus did Al- Fārābī’s De Intellectu find its way to becoming a major influence on both Latin and Hebrew theology from the late 12th and early 13th centuries on.

Katja Krause, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science & Technical University, Berlin

“Method in the History of Medieval Philosophy: What Good does it Serve?”

Abstract forthcoming

Edmund Lazzari, Duquesne University, USA

“Reading the Book of Nature: Quranic and Bonaventurian ayāŧ/similitudines of God in Nature”

The Qur’ān and the work of St. Bonaventure both prominently feature the concept that the natural world is significative of the divine. This paper will present aspects of each approach as they relate to the function of the natural world in Islamic and Christian thought. The paper will explore the role of metaphor in the significative aspects of nature, the theological significance of the non-rational world, and intelligibility of nature (including the symbolic meaning of mathematics). The paper will conclude with a consideration of the utility of these traditions to contemporary Muslim-Christian dialogue in science-engaged theology.

Luis López-Farjeat, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico

“The literal (ῥητή or φανερά / ẓāhir ) and the hidden (ὑπόνοια / bāṭin) in Philo of Alexandria and the Islamic philosophical tradition”

In his well-known work on Philo of Alexandria, Harry A. Wolfson argues that Philonic philosophy is the preamble to the “religious philosophies” of the three Abrahamic traditions. Among several coincidences and similarities between Philo and each of the religious philosophies, Wolfson highlights one particularly important: all three traditions found in their respective Scriptures two meanings, one literal (ῥητή or φανερά) and one hidden (ὑπόνοια). Each of these philosophical traditions sought —in its own way— an allegorical method of interpretation. Such a method was learned directly from Philo by the Church Fathers. And from the Church Fathers, it would have been transmitted, according to Wolfson, to Islam and Judaism. The most widespread version among historians of philosophy has been that neither Islam nor Judaism had direct contact with Philo. In any case, it could have been an indirect influence. Despite the ambiguities in this regard, this presentation aims to elucidate possible similarities between the notions of ῥητή or φανερά and ὑπόνοια and their Arabic equivalents, ẓāhir and bāṭin.

Martin, André, Post doctoral researcher Charles University, Prague (PhD, McGill 2022)

“Averroes’ Agent Sence in the Early 13th Century: Albert and his Sources.

Abstract: In Averroes’s Long Commentary on the De anima (II, c.60), Averroes tentatively argues for an “extrinsic mover” in sensation, analogous to Aristotle’s so-called “agent intellect”. However, Averroes leaves the exact nature of this “agent sense” unclear. E.g. where is it and exactly how does it function? In this paper I examine what seems to be the earliest discussion of this idea, from Albert the Great’s InDA (c.1254-7), back to Albert’s earlier sources, which seem to include Robert Grosseteste and his circle of Oxford Franciscans. In particular, I show that Albert does not do justice to the complexity of his sources.

Irfan Omar, Marquette University, USA

“Abū’l ‘Alā’ al-Ma‘arrī’s Philosophical Critique of Religion”

Al-Ma‘arrī (d. 1058 CE), the Syrian poet and philosopher who lived during the waning years of the Abbasid empire is a perplexing thinker. On the one hand, he lived an ascetic life, apparently, due to religious piety; on the other, he was fairly critical of religion. His critique was leveled against practices in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam; in that, he was an equal-opportunity offender. He particularly questioned, even mocked, customary Islamic understandings of heaven and hell, and derided many social norms of his time. In his poetic works he was able to couch his criticisms in the shadow of ambiguity using imagery, symbolism, and figurative expressions, however his philosophical critique of religion as well as his “skeptical humanism” (Britannica Academic, s.v. “Al-Maʿarrī,”) is fully revealed in his Risālat al-ghufrān, a work that describes al-Ma‘arrī’s imaginary visit to paradise which, he discovers, is filled with people whom the doctors of religion would brand as “heretics.” This paper examines al- Ma‘arrī’s method of critique as particularly “secular” and yet it was not aimed at eliminating religion. Using Sherman Jackson’s notion of the “Islamic Secular” (Oxford 2024), I would argue that al- Ma‘arrī was not anti-religion; rather he wished to reframe religion, Islam in particular, by looking at it through a philosophical lens, pointing to (what must be obvious to him) the space for secular reasoning within. Thus, in addition to its satirical and aesthetic value, Risālat al-ghufrān offers a glimpse of a version of Islam that appears to include not only the non-Muslim but also the non-religious.

John Peck, S.J. St Louis University, USA

“Thomas Aquinas’s Prime Matter Pluralism”

Prime Matter Pluralism (PMP) states that while the prime matter of all terrestrial bodies is the same, there is a unique prime matter for each celestial body. Prime matters are distinct in virtue of being in potentiality to different forms. According to Steven Baldner, in his early career Thomas Aquinas followed Averroës, who held that although celestial and terrestrial matters differ, only terrestrial matter is prime matter. Later, in Summa theologiae I, he endorsed PMP, claiming that there is a distinct prime matter for each celestial body. Finally, Baldner argues, Aquinas rejected PMP in his De caelo commentary and De substantiis separatis. Besides exegetical evidence for Aquinas’s ultimate rejection of PMP, Baldner presents a philosophical objection to PMP: according to PMP, distinct prime matters are restricted in their respective potentialities; such restriction requires form, however; therefore, prime matter is not pure potentiality. Since prime matter is pure potentiality, PMP is false. Pace Baldner, I argue that Aquinas endorses PMP as heartily in the later works as in STh I. Moreover, he resisted substantially the same objection to PMP as Baldner’s several times. In particular, Aquinas repeatedly rejected the claim that the restriction of prime matter’s potentiality requires form. In that case, when Aquinas calls prime matter “pure potentiality,” he means that it is formless of itself, not that it is in potentiality to any form whatsoever.

Ibrahim Safri, University of Heidelberg, Germany

“Motion in Categories in Pre-modern Islamic Philosophy”

In this paper, I will present how pre-modern Islamic philosophers engaged with theory of motion. Influenced by their atomistic theory, they formulated multiple definitions that correspond with this theoretical background, aligning nearly with the developed notion of motion. This perspective suggests that motion and rest are opposite and rely upon the sequential renewal of accidents. According to Aristotle, change is embodied in respect of substance, quality, quantity, and place. In contrast, modern kalām scholars’ interpretation posits that motion or change pertains restrictively to the category of place, thereby challenging the inclusion of the categories of substance, quantity, and quality.

Randal Smith, University of St Thomas, Houston, USA

“The Natural Law and Thomas Aquinas’s Debt to Maimonides”

It would be hard to overestimate the profound influence Maimonides had on the development of moral theology in the thirteenth century. So, for example, although in the Sentences of Peter Lombard, there is only one passing reference to the natural law, in Thomas’s Commentary on the Sentences, there are 173. It is not often recognized that, although there were discussions of the natural law among canon lawyers in the twelfth century, there was little interest in the natural law among theologians. By the time John de La Rochelle wrote his de legibus and Albert the Great his Summa de bono in the early thirteenth century, they included entire sections on the natural law. Clearly something had changed.

What changed, I would suggest, was the profound influence that Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed had on Latin Christendom. The work of this twelfth century Jewish philosopher was very quickly translated and widely disseminated. The Guide became especially popular in and around Paris because of its adoption by William of Auvergne, a respected theologian who became bishop of Paris. In this paper, I trace Maimonides’s influence from the Guide for the Perplexed to the Summa theologiae of Thomas Aquinas. I show that it was Maimonides’s effort to show the rational “reasons” of the Mosaic Law that inspired Christian exegetes to try to do the same. And it was this interest in the literal meaning of the Mosaic Law that caused thirteenth century theologians to incorporate into their work reflections on the natural law that had become common among the canon lawyers.

Francisco J. Romero Carrasquillo, St. Gregory the Great Seminary , Seward, Nebraska, USA

“The Multiple Meanings of Sacra Doctrine in Aquinas Seen Through Averroes’ Doctrine on the Levels of Discourse”

In the very first question of the Summa theologiae, Aquinas seems to use the term ‘sacra doctrina’ equivocally, to refer to the general presentation of Christian teaching, to the academic study of revelation, and as a synonym for Sacred Scripture. It would be difficult to grant the status of science to all these senses of the term sacra doctrina. Averroes also has a tiered understanding of religious discourse, which he presents in terms of the different levels of Aristotelian discourse—demonstration, dialectic, rhetoric, etc. In this paper, I use Averroes’ presentation as a useful comparison for interpreting Aquinas’ own understanding of sacra doctrina as a polysemic term. I argue there is a parallel between these two authors, and that Aquinas understands sacra doctrina as having within it different levels of discourse, some of which are demonstrative and others dialectical, rhetorical, and poetic. Therefore, not all sacra doctrina qualifies as a subaltern science, but only those parts that are demonstrative.

Adam Takahashi, Kwansei Gakuin University, Nishinomiya, Japan

This paper examines Albert the Great’s Commentary on the Sentences (1240s), focusing particularly on its second book, in which he distinguishes biblical angels from celestial intellects and addresses miracles within this world. Albert maintains that divine grace serves as the ultimate foundation of existence, surpassing the natural order as understood through philosophy. By investigating the tensions between Arabic Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology in this treatise, I argue that Albert develops a distinctly theological conception of the world, which he opposes to Aristotelian reasoning about natural causality.

Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, USA, & KU Leuven, Belgium

“A Critical Examination of Ibn Rushd on Matters of Philosophy and Religion”

In the present contribution I leave wholly aside concerns of the Medieval Latins and their interpretations and I argue for the importance of following closely the very words of Ibn Rushd regarding the natures of philosophical scientific discourse and of religious discourse and the necessity of distinguishing these through their ends. The end of the former is the determination of truth regarding God and all that is in the world. The end of the latter is the formation of a moral framework in which human beings may form themselves and their societies in righteous fulfillment of their natures in relation to God. Only in societies properly formed through religion can human nature be properly formed so as to allow the attainment of happiness by its members and to allow human individuals of excellence to reach their highest goal of intellectual knowledge of God and His creation. What follows here is in three steps. (1) I will first present some of the philosophically reasoned doctrines of Ibn Rushd which are in tension with common teachings of his religion. Next (2) I will provide a brief account of what Ibn Rushd presents as methodology in matters common to both philosophy and religion and the distinction of what is to be understood as ẓāhirī (evident) and what is to be understood as mu’awwal (interpreted). Finally, (3) I will draw some conclusions in regard to the issues discussed.

David Twetten, Marquette University, USA

“Aquinas’ Novel Definition of ‘Universal’ and Its Background in Avicenna: How to Answer ‘Universal Realism'”

Contemporary Aristotelians are well known for holding that for Aristotle, universals are real: they are instantiated or exemplified in particulars (notice the Platonic language). For example, Socrates is pale; courage (in Socrates) is a virtue. But what is a universal? Is it a predicate, or what a predicate signifies, which has content stability across instances? The medieval tradition of moderate realism, whose roots are in Alexander, distinguishes the predicate and its significatum from the universal. Universals, for Alexander, are only in the intellect (which is one for all humans). But what is the universal? Aquinas affirms a novel definition of the universal as distinct from a common nature (a distinction found in Alexander, Simplicius and Avicenna alike), which allows the universal to be in a plurality of intellects (as must be the case). The paper isolates the elements of this not often noticed definition, and traces its origin to Arabic philosophy and Avicenna.

Tracy Wietecha, Technical University, Berlin, Germany

“The City as A Mirror of Virtue: The Influence of Averroes on Albert the Great’s Conception of Virtue”

In his Long Commentary on the Metaphysics, Averroes writes that not all humans are inherently good or bad. Albert the Great integrates this idea into his ethics and politics, linking virtue to education and roles within the medieval city. Only those engaged in the city’s political life are subjects of moral virtue. This influence extends to Albert’s homiletic teaching, as seen in sermons to the Canons of St. Augustine. There he cites Averroes in calling the Canons to exemplify virtue for the rudes to emulate. This paper examines how Albert, inspired by Averroes, uses the city—both as a physical and metaphorical space—to form his ethical, political, and homiletic teachings on virtue.

Brett A. Yardley, DeSales University, USA

“Can ‘Pseudo’ Authors be Trusted?”

Ancient and Medieval thinkers accept testimony insofar as the speaker possesses “trustworthiness” accounting for accuracy and honesty. Many authors adopted the mantle of a renowned figure in disseminating their ideas. Using Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, whom Thomas Aquinas regarded with quasi-biblical authority, I explore whether and on what grounds listeners can trust “pseudo” authors including qualities and circumstances surrounding author and audience including: culturally accepted genres, literary devices, and authorial intent—including deceitful promotion—on rational acceptance in light of literary awareness, chronological or authorial misattribution, and/or continued belief after corrected authorial identity.

Patrick Zoll, S. J., Munich School of Philosophy

“Can We Know the Essence of a Simple God? Thomas Aquinas’s Critique of Maimonides in De potentia“

It is uncontroversial that Thomas Aquinas distinguishes between esse, which signifies the truth of a proposition (veritas propositionis), and esse, which signifies the actuality of a thing (actus essendi), to refute the claim that knowledge of the fact that God is or exists (an est) implies that we know God’s esse and consequently God’s essence (quid est). Scholars often assume that this critique commits Aquinas to a negative theology, according to which we cannot have knowledge of God’s essence. In my paper, I argue that a close examination of Aquinas’s critique of Maimonides in De potentia shows that this is a misinterpretation. The fact that we cannot have perfect knowledge of God’s essence does not exclude the possibility that we can have imperfect knowledge of the essence of a simple God.

Accommodations Advice and a Little Travel Advice from Dr DeHaan

If someone prefers all the American comforts, there is a good hotel a few blocks away: the Premier Inn Oxford City Centre (Westgate) hotel. https://www.premierinn.com/gb/en/hotels/england/oxfordshire/oxford/oxford-city-centre-westgate.html?cid=GLBC_OXFORD

A little bit further walk away is the: Courtyard Oxford City Centre Hotel, 15 Paradise Street, Oxford, OX1 1LD United Kingdom https://www.marriott.com/en-gb/reservation/rateListMenu.mi?gclid=Cj0KCQiAkoe9BhDYARIsAH85cDPMvsWD–yAydw38iHs_Ywt5UHWyAHjGN86R86JErvMiCpJZ3jfTmEaAjZYEALw_wcB&dclid=CKONgp-lqosDFUxIHQkdVYkeIg

Here are options that you could share straight away as it is public information already available online:

Rewley House has a lot of rooms for University guests and at good rates but you’ll want to book ahead of time. It is in the city centre and really close to Blackfriars where we will be on Friday. https://www.conted.ox.ac.uk/about/accommodation

Rewley house is a bit of a walk to Campion Hall from there; I could do it in a brisk 10 minutes. Google says 13 minutes.https://maps.app.goo.gl/245VfR5o8zZYdtbD8

There are often good rates for those wanting to stay a few nights in one of the other Oxford colleges if one books early. Like 3-6 months in advance. This website is what everyone uses: https://www.universityrooms.com/en-GB/city/oxford/home

Finally, there is a newish budget hotel in the Summertown neighborhood on the northside of Oxford. https://www.easyhotel.com/hotels/united-kingdom/oxford/oxford

I would probably only recommend this to graduate students since one would need to take a bus to the city centre from there (or walk 40 mins), but it is a very straightforward bus service with many buses serving City Centre to Banbury road stops all day and night probably 5-8 buses every hour (I live on this route and take it every day into work).

There are many other hotels, airbnb locations, and bed and breakfasts in the Oxford area, but these are places that are typically more affordable and easy to access from the train and/or bus.

On that, see: https://welcome.ox.ac.uk/getting-around

To/From Oxford and Heathrow or Gatwick Airports I recommend this bus service: https://www.theairlineoxford.co.uk/

I recommend NOT FLYING TO STANSTED. It is great for Cambridge, but Stansted Airport is very inconveniently located for getting to and from Oxford.

Restaurants near Campion Hall: Dishroom Permit Room Oxford; Fernando’s Cafe; Victor’s Oxford; La Taberna; The Bear Inn (pub)